Chickpea: Introduction

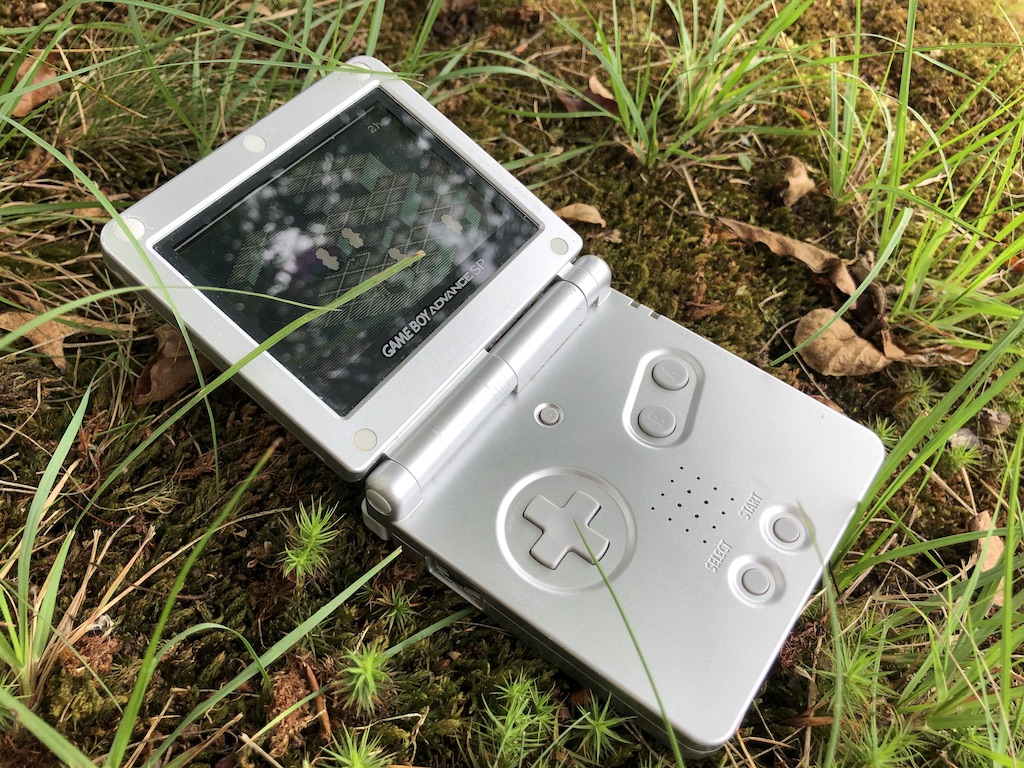

A Chickpea build running on a Game Boy Advance SP laying outside, surrounded by a variety of grasses and brown leaves, the screen partially obscured by the reflection of cloudy sunlight filtered through the trees overhead.

I created this blog mainly to document the creation of a game I’ve been working on. I’m still a while away from figuring out things like the game’s actual title, setting, story, themes and etc, but I’m calling it Chickpea for now.

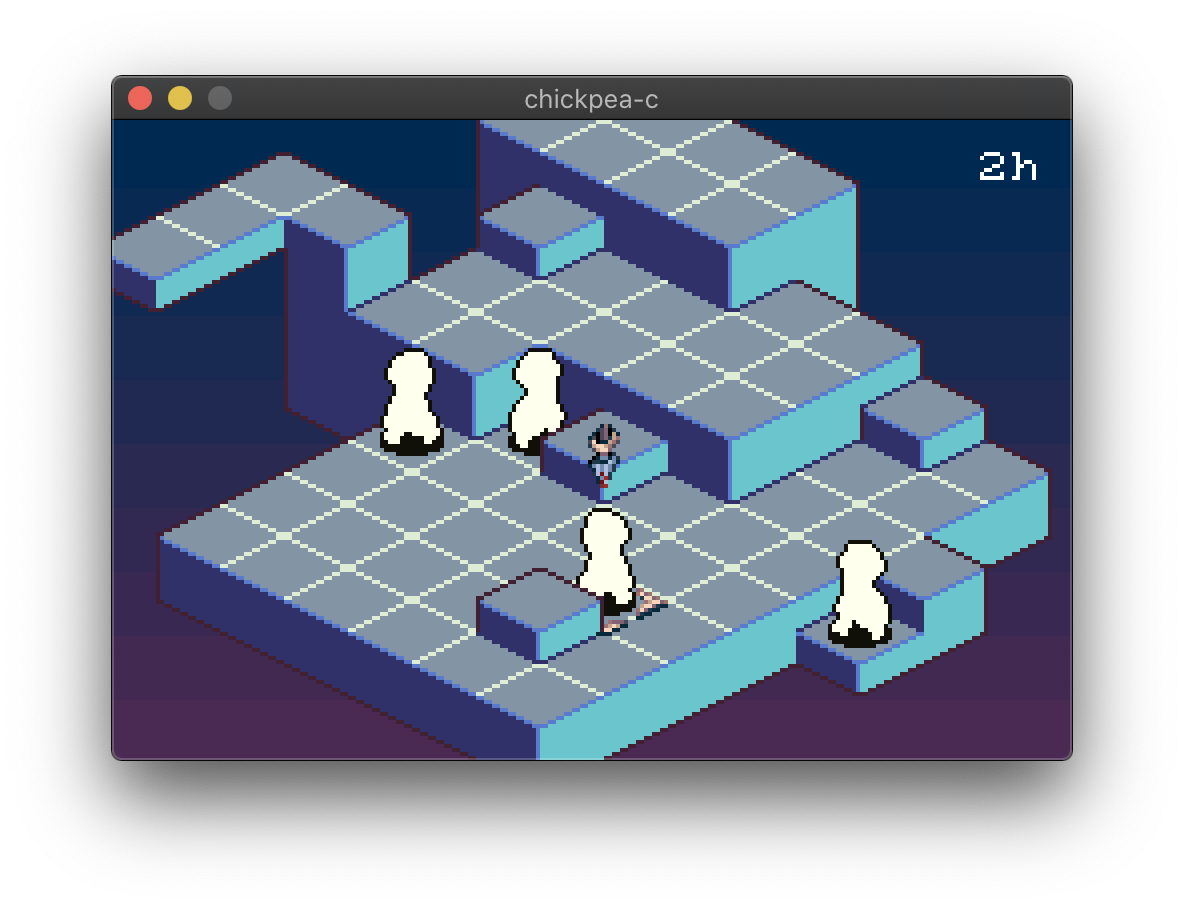

A screenshot of Chickpea running natively on MacOS, showing an isometric tilemap, with a cursor and blank characters positioned in the world.

I’ve long adored both strategy role-playing games, and games with isometric art in general, and for an embarrassing number of years I’ve started and stopped projects that would fit into this niche, some even using this same project name. I’m happy to say that I’m already further along then I’ve ever been.

To keep me focused and working under creative limitations, the game is being coded to run natively on desktop OSes, and on the Game Boy Advance. While this certainly entails some extra work, it has already been a boon to be able to debug code that isn’t emulated. I’m going to explain how I’ve decided to tackle this architecturally, and the consequences of these design decisions.

But, how do you program a Game Boy Advance in the first place?

Programming the Game Boy Advance

The Game Boy Advance (GBA) has a 16.78 MHz 32-bit ARM CPU, a generous 288 kilobytes of general purpose RAM, and 98 kilobytes of video RAM.

Like a lot of older game consoles, there is no operating system, and everything you want to do from displaying graphics on the screen, to sound and user input happens by reading and writing to specific locations in memory, often called registers or I/O registers to diffentiate them from CPU registers.

Here’s an example of one of the most important I/O registers, that controls various aspects of the GBA’s display. All of this information is taken from the wonderful GBATEK document, which is an invaluable resource for anyone who wants to program the GBA or Nintendo DS.

4000000h - DISPCNT - LCD Control (Read/Write)

Bit Expl.

0-2 BG Mode (0-5=Video Mode 0-5, 6-7=Prohibited)

3 Reserved / CGB Mode (0=GBA, 1=CGB; can be set only by BIOS opcodes)

4 Display Frame Select (0-1=Frame 0-1) (for BG Modes 4,5 only)

5 H-Blank Interval Free (1=Allow access to OAM during H-Blank)

6 OBJ Character VRAM Mapping (0=Two dimensional, 1=One dimensional)

7 Forced Blank (1=Allow FAST access to VRAM,Palette,OAM)

8 Screen Display BG0 (0=Off, 1=On)

9 Screen Display BG1 (0=Off, 1=On)

10 Screen Display BG2 (0=Off, 1=On)

11 Screen Display BG3 (0=Off, 1=On)

12 Screen Display OBJ (0=Off, 1=On)

13 Window 0 Display Flag (0=Off, 1=On)

14 Window 1 Display Flag (0=Off, 1=On)

15 OBJ Window Display Flag (0=Off, 1=On)

I won’t explain all of these details, but, in the top line that first number 0x0400_0000 is the address of this I/O register, and DISPCNT is the traditional name for it. It’s a 16-bit value at that address, so, if we wanted to display the first background (BG0), we could write C code like this to do so:

#define DISPCNT (*((volatile uint16_t *)0x04000000))

void enable_bg0(void)

{

DISPCNT |= 1 << 8;

}

The define casts 0x04000000 to a pointer and then dereferences that pointer, allowing it to be used almost like it was a global variable.

Chickpea’s Abstraction Layer

In Chickpea, there are two seperate header files that contain definitions much like the one above. One header is for the desktop OS build, and another for the GBA. There’s a common header file that conditionally includes the correct one of these.

// chickpea/gba.h

#define REG_DISPCNT (*((volatile uint16_t *)0x04000000))

This is identical to before, except for the REG_ prefix.

// chickpea/emulated.h

extern uint16_t reg_dispcnt;

#define REG_DISPCNT (reg_dispcnt)

For the desktop OS build, we instead define a global variable to represent the I/O register, and the pre-processor definition references that.

Instead of having to remember what bit 8 does, we can introduce some defines for each field of the register:

// example.c

#include "chickpea.h"

void enable_bg0(void)

{

REG_DISPCNT |= DISPCNT_SCREEN_DISPLAY_BG0;

}

Now, though this code will compile on all platforms, and work on the GBA, it won’t do anything on a desktop platform without code to emulate the effects of what writing to this register does on the GBA.

Here’s the first conundrum, when does it do something? On the GBA it will enable the background BG0 to be drawn immediately, even mid-screen render. This is because the graphics hardware is constantly operating even when your code is running. Though the GBA’s CPU only has one thread of execution, the hardware rendering the game is in some sense a co-processor that you are communicating with through the REG_DISPCNT register.

Game Boy Advance Rendering

The GBA renders in a line by line fashion, with small breaks between each line of pixels and a larger break at the end after it has finished drawing the full frame. The small break after each line is called an H-blank or horizontal blank, and the big break at the end is called the V-blank or vertical blank. While you can always read and write the various I/O registers, video memory (VRAM) is only accessible during the horizontal and vertical blanks when the graphics hardware isn’t reading from it.

Because of this, the timing of some of the code in your game is important. We can’t do everything we want while the GBA is rendering, but we can defer modifications to VRAM until one of these horizontal or vertical blanks happen.

Here’s how this could look at a high level:

// This code can run at any time

void update(sprite_handle sprite)

{

uint32_t frame = /* calculate the next frame of animation somehow */;

// Add a pointer to the next frame of animation into some sort of queue

// for later, but don't do any copying into VRAM just yet.

sprite_queue_frame_copy(sprite, &spritesheet[frame]);

}

void on_vertical_blank(void)

{

// Copy the graphics data into VRAM, emptying the queue

sprite_execute_frame_copies();

}

Thankfully the GBA can tell us when it is in either H-blank or V-blank through a couple of bits in different I/O registers that we can check ourselves in our code, or through interrupts, which is a way for the CPU to immediately stop our currently executing code and begin executing a callback we define called an interrupt handler. In our interrupt handler, we could call on_vertical_blank() after determining that the cause of the interrupt was a vertical blank happening.

The First Conundrum, Again

So, when does writing to REG_DISPCNT (or any I/O Register) do something on the desktop OS build? Right now, its when you call halt().

The GBA has a number of built in Basic Input/Output System (BIOS) routines for convienence sake, one of these is called halt(), and it switches the CPU into a low-powered state while the rest of the device remains operating. halt() returns once an interrupt you have requested to be notified of happens. This is handy not just for helping to time your code, but to decrease the amount of power your game uses so your battery lasts longer. It is a portable handheld, after all.

Here’s how your game’s main loop could look, again at a pretty high level:

static bool needs_update = true;

void main(void)

{

enable_vblank_interrupt();

while (1) {

if (needs_update) {

update();

needs_update = false;

}

halt();

}

}

void on_vertical_blank(void)

{

write_updates_to_vram();

needs_update = true;

}

We have an update() function that we want to call once per frame, so every time we wake up we check to see if we need to run it, and otherwise go back to sleep. Assuming enable_vblank_interrupt() sets up on_vertical_blank() to be run when the V-blank happens, it will be called once per frame, do what it needs to do, and then set needs_update back to true. Then when the CPU resumes where it left off, returing from halt(), even if it is still in V-blank, it can call update() again and start working on whatever gameplay logic needs to happen for the next frame.

Now, on the GBA halt() would call the correct BIOS routine, but on a desktop OS we can define it ourselves to do something very different than halting. Here’s some more pseudo-code:

void halt(void)

{

while (1) {

// Emulate all the graphics, input, etc hardware, setting some

// variables if an interrupt needs to happen.

emulate_hardware();

if (vblank_triggered && vblank_interrupt_enabled) {

on_vertical_blank();

return;

}

else if (hblank_triggered && hblank_interrupt_enabled) {

on_horizontal_blank();

return;

}

}

}

Inside emulate_hardware() is a state machine that goes back and forth between all of the steps in the rendering process. Rendering a line, then trigger a H-blank, then render another line the next step, then trigger another H-blank. Eventually present the frame to the screen and trigger the V-blank.

Consequences of The Design

This is very different from how a GBA emulator would work. Since we’re running normal, non-emulated code, in a single threaded manner, we need points where we can stop and simulate what the hardware should have already done. A full GBA emulator, on the other hand, would be able to run whatever code it wanted, in between each emulated CPU instruction or cycle, and it could keep track of timings precisely.

Even though virtually the same program (in terms of source code) can run on both the GBA and the desktop with this design, there’s no guarentee that an arbitrary program would work on both. A trivial example: You could write a GBA game that never calls halt() that would function just fine on the GBA, but on the desktop using this framework it would never do anything because emulate_hardware() would never be called.

Further more you could write code for the GBA that couldn’t possibly work under this framework. You could write precisely timed code to enable a background mid-line by writing to REG_DISPCNT, but emulate_hardware() renders an entire line at a time inside of halt(). That would be a strange thing to do, I think, but you could.

Even more suspect, is that there’s no real sense of timing outside of halt() in the desktop OS version. Your code practically has an infinite amount of time to run, both the ‘main thread’ and in the interrupt handlers. On the GBA with it’s 16.78 MHz CPU, how long your code takes is a very real concern, an H-blank in particular is only 272 CPU cycles long.

Conclusion

Ultimately with how this project is structured, it is going to be a constant negotiation between how I write the game and how the hardware is emulated. I’m constantly testing out any changes and new additions on a GBA emulator primarily, and then making sure the desktop OS version matches.

There is the possibility that some feature I haven’t gotten to yet in the GBA hardware will cause me to revisit or revise parts of my approach, especially around timing. But I don’t think any of it will be insurmountable.

Being able to run natively on desktop OSes has a lot of boons compared to just running the game in an emulator. Full feature debuggers and various runtime code sanitizers are available, and due to the hugely disperate CPU speeds, you can go wild with expensive assert statements and even logging potentially.

The biggest downside is needing to be able to understand the hardware enough to more or less write a bespoke GBA emulator for whatever features of the hardware you use. Thankfully, there are a ton of excellent documents like GBATEK and plenty of open source GBA emulators to study. In particular, I don’t think developing this game like this would be possible without mGBA, both as an emulator full of useful debuggining functionality, and as code to study.